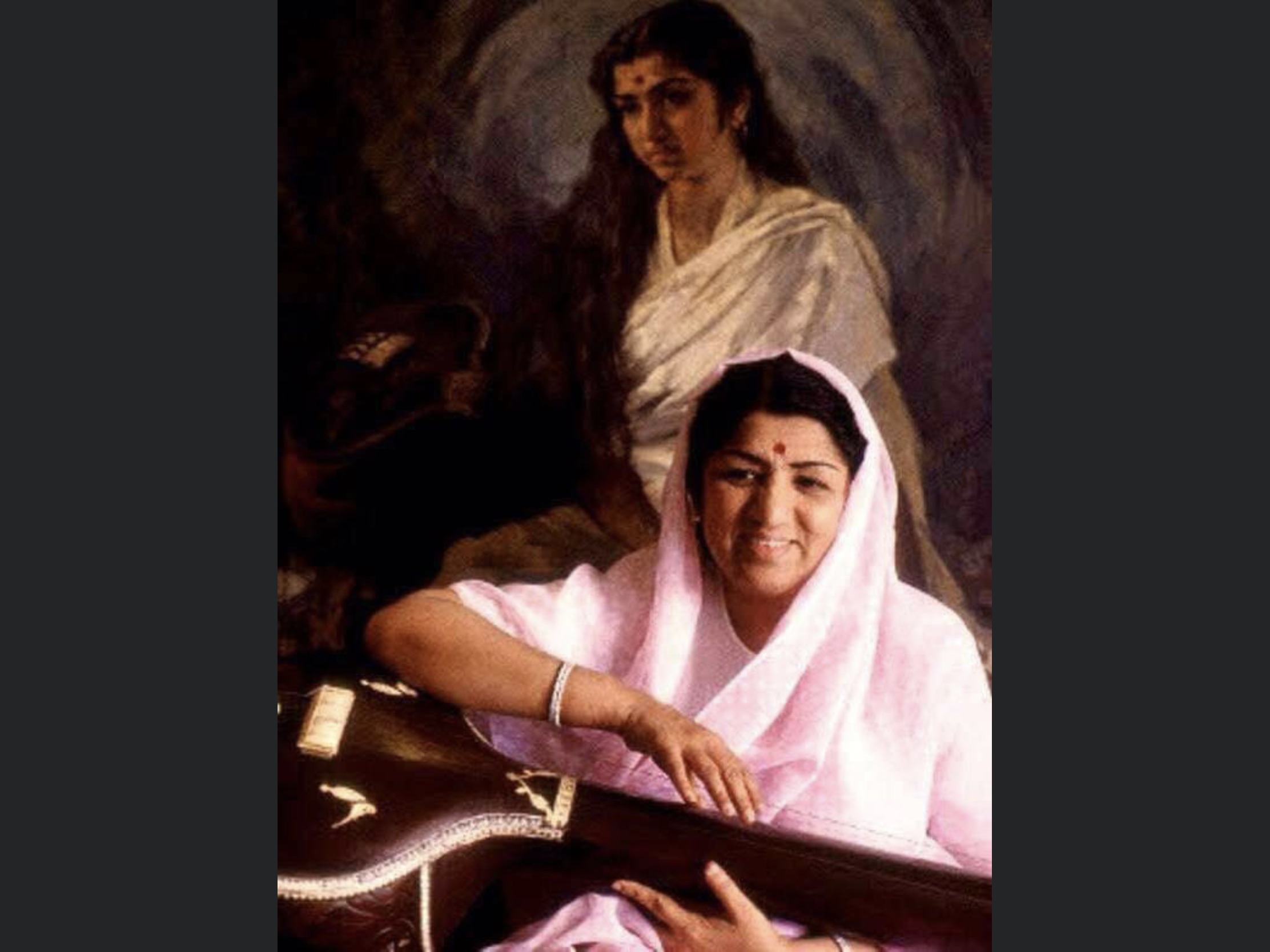

Lata Mangeshkar, born Hema Mangeshkar had been given several honorifics – Nightingale of India, Queen of Melody, and so on, all of them good as descriptions go but none that truly described her. She was phenomenal.

Losing her father when she was only thirteen, in 1942, the burden of providing for her three siblings and her mother fell upon her slender shoulders. Her father’s friend Acharya Vinayak came to her support by offering small parts in the films he made. So, Lata came to initially act, and then sing in a few Marathi films. It was a hard life, not helped by the death of Vinayak in 1947. Lata scrounged around for small singing roles in films. She also took up a study of music with Ustad Aman Ali Khan.

It was music composer Ghulam Hyder who, impressed with her voice, took her to meet the producer Shashadhar Mukherjee. Mukherjee rejected her finding her voice too thin. The reigning divas of Hindustani song then were Noor Jehan, and later Suraiya. In Western classification they would be called sopranos. Lata was at best a Sopranino, a voice outside the range of Western operatic music certainly but also too high pitched for Indian tastes of the time. Even after Lata Mangeshkar matured as a singer and began to sing in her own natural pitch, she never really got below the level of a soprano coloratura.

The initial years saw her copying the then prevalent style of female voice. It was Khemchand Prakash who first unleashed the true Lata pitch upon an unsuspecting world. That was the song ‘Aayega aanewala’ in the supernatural mystery film ‘Mahal’, with which a nubile Madhubala enchants a doomed Ashok Kumar.

There was no looking back after ‘Mahal’. One by one the icons of yesteryear fell by the wayside. Noor Jehan was forgotten, Suraiya abandoned. Shamshad Begum eclipsed. Soon, it became impossible for even accomplished voices to break into the female Hindi film genre. Geeta Dutt (nee Roy) was confined to a niche. Sudha Malhotra survived on leftovers, Meena Kapoor hardly got a look in before she was discarded. Kamal Barot and Suman Kalyanpur struggled for a while in the sixties but eventually abandoned the race.

The trouble was that music directors were smitten with Lata. They wrote music for her pitch and her voice. Naturally no one else could do what she could. Raju Bharatan, the well-regarded critic of Hindi cinema wrote that Hindi film music composers got together and hunted all over India for a replacement for Lata, but failed. By now she had become a bit of a prima donna and was not above letting the music directors know her worth.

It is said she kept down the competition by threatening to boycott composers who used any other female voices. And no one dared, except the maverick Lahori O P Nayyar. OP Nayyar used Lata’s sister Asha Bhosle and built his reputation bypassing Lata entirely. Even the great S D Burman had to endure a five year boycott by Lata Mangeshkar when they fell out in 1957. In the 60s Lata quarrelled with the genial Mohammad Rafi over royalties. She wanted a share in the royalties received after a song had been rendered and paid for. Rafi felt that the one time payment received for singing a song was enough. The famous duo did not get together again for nearly 20 years, and then only shortly before Rafi’s death.

If Lata Mangeshkar was a prima donna she had every right to be one. Her voice, though pitched higher than the norm at the time, was perfect. By perfect I mean that it was flawless. In decades of listening to Lata, on radio, shellac records, lp records, tape and CD it has been near impossible to detect a false note. She sang effortlessly, and in her best songs she was sublime. No wonder Bade Ghulam Ali Khan remarked of her, ‘kabhi besura gaati hi nahi’.

One wonders what she would have done as a classical singer, had she gone down the path of, say, Kishori Amonkar or Prabha Atre. One cannot realistically imagine Lata emulating Kishori’s ‘Raag Bhoop’ or Prabha Atre’s ‘Maru Bihag’, but equally, I doubt if either of the two classically trained singers could have executed some of Lata’s faultless songs. Imagine, if you can anyone but Lata sing Rasik Balma from ‘Chori Chori’, or ‘Bekas pe Karam kijiye’ from ‘Mughal-e-Azam’. Could anyone else have managed ‘O Basanti Pawan Pagal’, except the peerless Lata Mangeshkar? Could anyone else have rendered ‘Aaja re Pardesi’, but Lata?

These days it is easy to compare contemporary singers with so many easily available remixes. You can even compare Lata with Asha her sister and judge for yourself. Summon on Youtube that old favourite ‘O Chand jahan wo Jayen’ from the fifties film ‘Sharda’ picturized on Meena Kumari and Shyama and sung by the two sisters respectively.

It is unimportant if Lata Mangeshkar sang 10,000 songs or 30000. We judge Lata by quality not quantity. She sang in many languages and always with perfect pronunciation. How beautifully did she render in Dogri, ‘Bhaleya Sipaiya Dogreya’, the plaintive cry of a lovelorn girl missing her soldier lover the spring bedecked hills. Her Bengali output, a lot with Salil Chowdhury, is as unmatched for vocal purity of it is innovative technique. Her Urdu was word perfect. Afficionados will recall her renditions of Ghalib’s ‘Har ek Baat pe kehte ho ki tu kya hai’ or Iqbal’s ‘Kabhi ae Haqiqat e Muntazir’.

In later years her voice thickened a bit. Those who heard her sing in the nineties in the Bollywood dramas like ‘Dilwale Dulhaniya le Jayenge’ will have noticed. Age of course brooks no argument. In the decades of her prime Lata was unequalled, without a rival, and indeed without a challenger. We can enjoy Shreya Ghoshal, a great singer, emulate Lata Mangeshkar in ‘Lag Ja Gale’, but we know instinctively, from the very first note that it is not the same thing. There will never be another singer like Lata.

The author is a retired IAS officer.

(Disclaimer: Views expressed above are author’s own.)