Delayed justice is better than no justice at all.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi inherited several separatist movements as a baggage of history and political malfeasance of his predecessors. While Khalistani movement was crushed in Punjab way before he assumed power, jihad in Kashmir, Maoism in the red corridor, and ethnic insurgencies in the northeast remained challenges in his first term. But by the second term, PM Modi created history and made unprecedented paradigm shifts in each of these areas.

He reorganised the state of Jammu and Kashmir, nullifying Article 370 and Article 35A — the instruments with which separatist sentiments had sustained for seven decades in Kashmir and consequently also led to terrorism sponsored by Pakistan. To resolve the five-decade old violent conflict in Assam over the demands for a separate Bodoland, the Modi government signed the Bodo Accord in 2020, ushering in a new era of peace in the state. An agreement was signed with National Liberation Front of Tripura (SD) involved in violence and operating from their camps across international borders.

Likewise, the government resolved the 23-year-old Bru-Reang refugee crisis in Mizoram (a large number of minorities Bru-Reang families had migrated to North Tripura in 1997-1998 due to ethnic violence in western part of Mizoram) by settling down more than 37,000 internally displaced people in Tripura. Several initiatives addressing the issues of tribals in an effective manner, brought down the incidents of Maoist violence by 70 per cent and Maoists who were actively operating from 96 districts in the country, are now shrunk to 46 districts.

READ MORE: Kashmiri women breaking glass ceiling in sports

While all this is great, Prime Minister Modi cannot feel reassured that these measures have resolved the challenges fully. What is worrisome is that some elements of the Khalistani movement – which was dead and alive only among the diaspora in the UK, the US and Canada –resurfaced in Punjab during chief minister Captain Amarinder Singh’s time and have hogged the limelight under the AAP government. Similarly, targeted killings of minorities in Kashmir have not generated confidence among the ethnically cleansed community of Kashmiri Pandit Hindus to consider their return to the Valley.

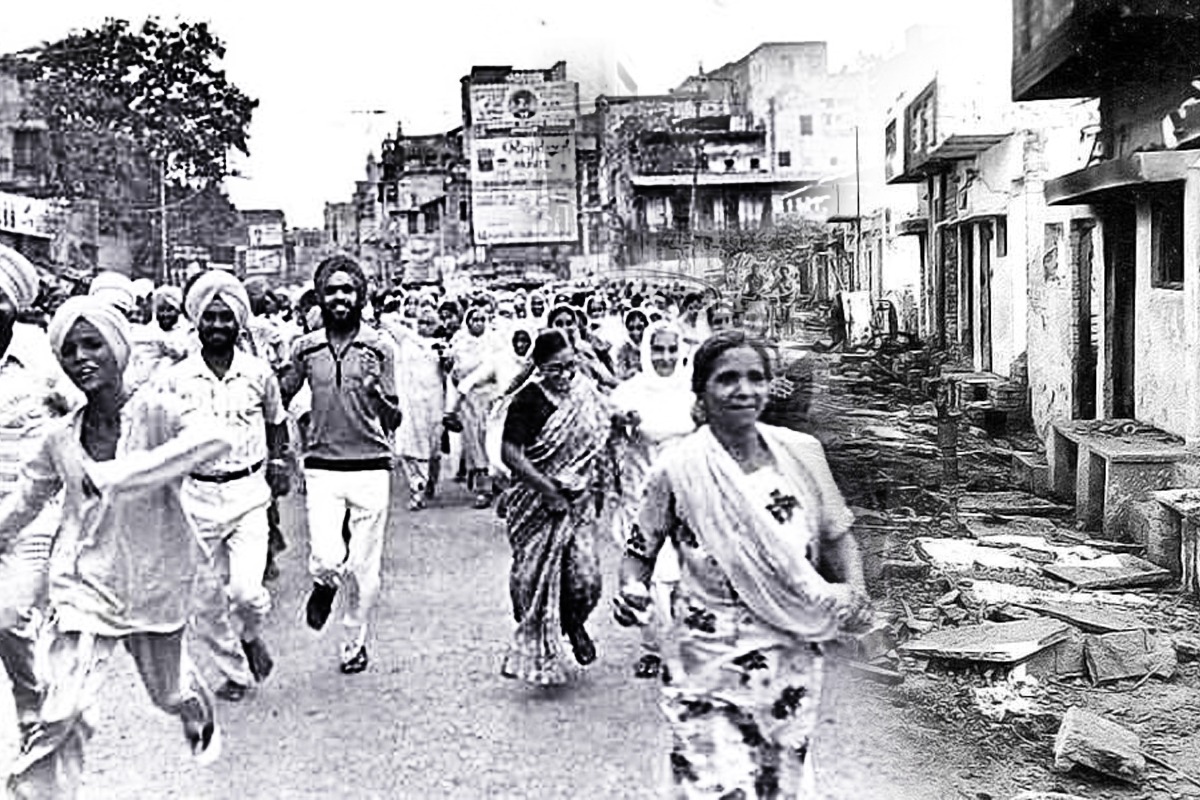

The events of 1984 in India, when over 3000 innocent Sikhs were brutally killed in the aftermath of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination and the ethnic cleansing of over 300,000 Kashmiri Pandit Hindus by jihadi terrorists in Kashmir in 1989-90, remain dark stains on the nation’s conscience. Several leaders from the Congress party instigated and condoned the 1984 violence against Sikhs. In the case of Kashmiri Pandit Hindus, the then chief minister Farooq Abdullah and the then Union home minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed under whose nose the ethnic cleansing began, with the backing from Jamaat-e-Islami in Kashmir, were never held accountable. The political influence has obstructed the course of justice in both the cases for far too long.

Families of the victims still bear the scars of the two tragedies, and the Sikh and Pandit communities have been left with a deep sense of injustice. There has been no closure on the carnage of Sikhs and ethnic cleansing of Pandits, since the political perpetrators remain scot-free. Without justice, there can be no true healing and reconciliation. The failure to bring the political culprits to justice has perpetuated a culture of impunity and has undermined faith in India’s judicial system.

Justice is not just about punishment; it is also about closure and reconciliation. Convicting the political culprits would send a powerful message that the Indian state is committed to upholding the rule of law and ensuring justice for all its citizens, regardless of their religious or political affiliations. It would demonstrate that India is willing to confront its past and learn from it, fostering a more inclusive and harmonious society.

Moreover, the pursuit of justice is essential to prevent such atrocities from happening again. The failure to hold political leaders accountable for their role in the 1984 massacre and the 1989-90 ethnic cleansing of the Pandits has set a dangerous precedent. It sends a message that politicians can manipulate religious and communal sentiments for electoral gains without facing consequences. Convictions in these cases would serve as a deterrent, making it clear that inciting violence for political purposes will not go unpunished.

READ MORE: India must not play bilateral matches with Pak until terrorism ends

Critics argue that pursuing justice for events that occurred decades ago is futile and that it may further divide communities. However, justice knows no statute of limitations, especially for crimes as grave as mass murder. Delayed justice is better than no justice at all. Reconciliation cannot be achieved without addressing the underlying wounds, and justice is an essential part of that process.

Some also contend that the victims and their families should move on and focus on the future rather than dwelling on the past. While it is important to look forward, justice is not about dwelling on the past; it is about ensuring that the past does not haunt the future. Convicting the political culprits would provide closure to the victims’ families and allow them to heal, making it easier for them to move forward with their lives.

In recent years, there have been efforts to reopen and re-investigate some of the cases related to the 1984 Sikh massacre and the Kashmiri Pandit Hindu ethnic cleansing. These are positive steps, but they must be pursued vigorously and without any political interference. Witnesses must be protected, evidence preserved, and trials expedited and brought to conclusion at an earliest.

Prime Minister Modi has to take tough calls on these festering wounds, if he wants to leave a legacy of a statesman who healed the nation and laid the foundation stone for a strong and stable civilisation of Bharat. He must set examples in both these cases.