Union law minister Kiren Rijiju recently suggested that Maharaja Hari Singh was willing to accede the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir to India in the summer of 1947, but then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru was unresponsive, since he wanted Sheikh Abdullah to have a leading role.

It is true that Nehru gave primacy to Abdullah with regard to the state. Abdullah had become an iconic leader, and Nehru thought he could represent a large majority of the Kashmiri people in the Valley.

Since the 1930s, the Congress had held that the peoples of the princely states in the British India should decide their fate, rather than their rulers. The new government of India had already applied this principle in Junagadh and would do so in Hyderabad state too.

So, Nehru wanted to be able to say that the J&K accession too was on the basis of the people’s will. He believed Abdullah was committed to secular and inclusive principles and failed to grasp that his friend had ambitions beyond India and Pakistan (independence).

When Abdullah’s manoeuvres from `49 onward (including meetings with US Ambassador Loy Henderson and Secretary of State Adlai Stevenson) showed what his friend was really upto, Nehru stood firm. The government went so far as to unseat and arrest the extremely popular Kashmiri leader in August 1953.

Considering all this, Nehru was wrong to have trusted Abdullah in the first place, and to have prioritised the aspirations of the Kashmiri people at the expense of other peoples of the state, which was extraordinarily diverse — geographically and sociologically.

After all, across the entire state, the population of the Valley was a minority, one that has contempt for its own minorities — and I mean minorities among Muslims in the Valley, such as Shias, Paharis, and Gujjars.

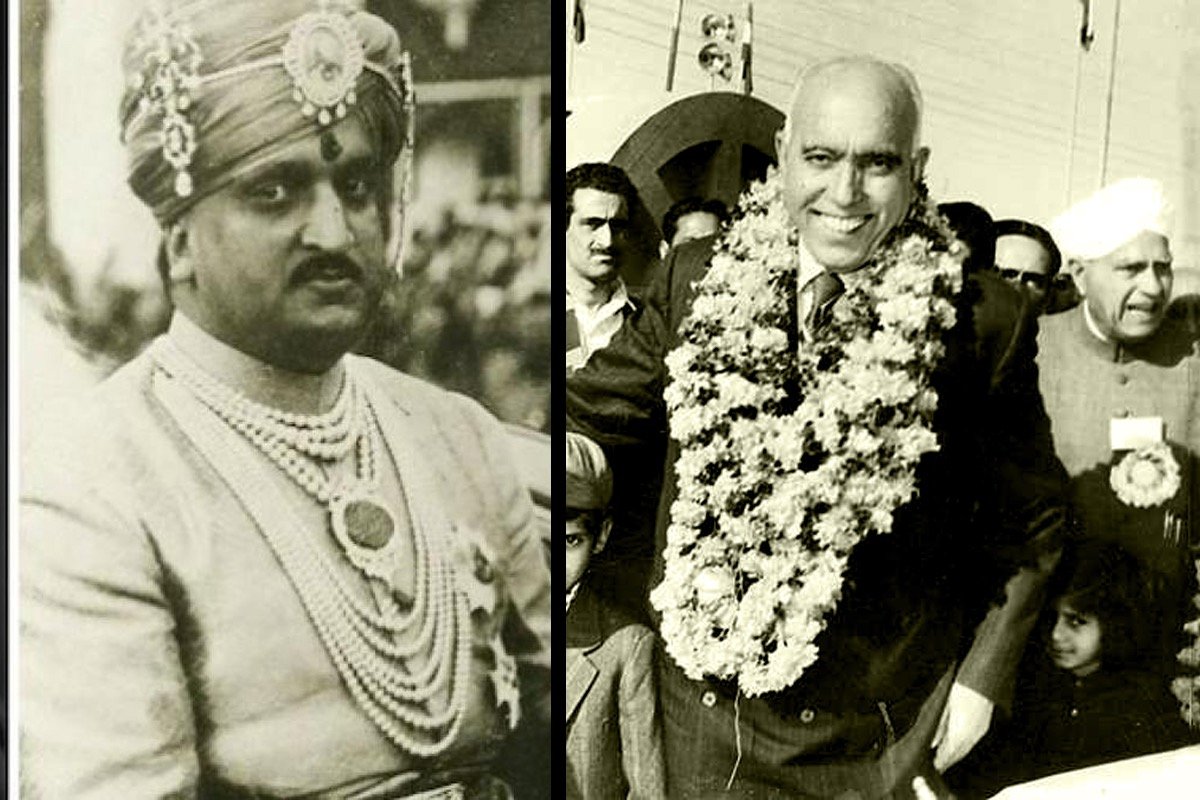

Maharaja’s vacillation

As for Maharaja Hari Singh’s intentions, I have seen no evidence during several decades of research that he wanted to accede to India. The law minister has pointed to a noting by Nehru that the issue of accession had come up when the Maharaja visited Delhi that summer, but has shown no direct evidence that the Maharaja had proposed to accede his state to India.

In fact, in what almost seems like a rebuttal, RSS leader Ram Madhav has cited a note from Nehru to the Maharaja which he says Mountbatten carried to Srinagar in June. “’The normal and obvious course appears to be for Kashmir to join the Constituent Assembly of India”, Nehru insisted in that note,’ Madhav wrote in a November 4 article.

According to Madhav, “none” of the Indian leaders was willing to leave J&K to Pakistan. Indeed, he cites Mahatma Gandhi saying: “The state had ‘the greatest strategic value, perhaps in all India’.”

When India and Pakistan became independent, the Maharaja proposed Stand Still Agreements to both new countries. It is on record that, while Pakistan signed that pact (and then flouted it), India turned it down.

The Maharaja remained noncommittal for three months after Mountbatten told all the rajas, maharajas, and nawabs on July 25 that they must accede to one of the two soon-to-be-independent countries, at least with regard to defence, external relations, and communication.

Even when Pakistan sent Pashtoon tribesmen into the state in large numbers on October 22 — basically to forcibly take it over — the Maharaja did not accede, only requested the government of India to send troops to help his forces to repel the attackers.

It was the government of India which responded that India could only send troops to defend Indian territory — if he acceded. This back-and-forth series of communications, caused by his reluctance to accede even at this stage, needlessly wasted time. The tribesmen might have taken control if they had not stopped for rape and pillage along the route to Srinagar.

Anecdotal records of what the Secretary for States, VP Menon, said when the Maharaja finally signed the accession document indicates that the government of India had been on tenterhooks about whether he would finally accede even when he and his family were in mortal danger.

Constitutional authority

Even when he did sign, the Maharaja sent a covering letter, stipulating that he was only acceding with regard to the three matters Mountbatten had (while he was still the Viceroy) stipulated as the minimum, and that the terms of this accession could not be changed except by him.

The Indian government acknowledged that in its acceptance letter and added that it was subject to popular consent. That opened the door to getting a mandate of approval for full and final accession from the people of the state.

Those who criticise Nehru for letting Abdullah appoint a constituent assembly for the state should realise that the resultant Constitution clearly stated that “Jammu and Kashmir is, and shall remain, an integral part of India.”

That constitution was finalised in November 1957, after Abdullah had been in jail for four years. Members of that assembly were treated to lavish comforts after his arrest, but great pressure, no doubt, lurked in the background. The net result was that the accession was given approval in the name of the people, and the state became an “integral part of India.”

One of the negative effects of the constitutional changes of 2019 was that the state constitution was needlessly thrown out of the window. For, that constitution also stipulated that the borders of the state as ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh could not be changed. They were unnecessarily changed by dividing the state into two union territories.

Road to independence

That Constitution’s assertion that the state was an integral part of India blocked what both Abdullah and the Maharaja had wanted around 1947.

The historical material available makes it evident that the Maharaja had hoped to find a way for the state to remain independent. His prime minister, RC Kak, whose sons were RAF pilots, is said to have recommended independence, or —second choice — accession to Pakistan. Those were Britain’s preferences. (The Maharaja had let Kak go after Mahatma Gandhi advised him during a meeting in Srinagar on August 8 to check whether his prime minister was popular.)

According to British versions, Sardar Patel had asked Viceroy Mountbatten to tell Maharaja Hari Singh in June 1947 on behalf of the government of India that India would not object if J&K joined Pakistan.

Mountbatten apparently carried this message when he visited Srinagar for five days (15 days after announcing partition) to urge the Maharaja to make up his mind either way at the earliest.

However, the Maharaja avoided a formal meeting. After fixing a meeting for Mountbatten’s last day there, he cancelled it, complaining of colic that morning.

Even if Patel was willing to reach an agreement with Jinnah in June to let J&K go in exchange for Hyderabad state in the immediate aftermath of the partition decision, he soon became one with Gandhi and Nehru on wanting J&K included in India.

Sardar Patel (and other leaders) could not have known in June that the border between the two proposed countries would allow a road link from J&K to the rest of India.

It was only when the Radcliffe Line dividing Punjab was made public on August 17 that it became physically possible for J&K to join India. The Maharaja hurriedly had a road constructed over the next couple of months from Jammu to the portion of Gurdaspur district that Radcliffe gave India. (Jammu had been connected through Sialkot until then.)

It is almost certainly Nehru’s influence with the Mountbattens that ensured that the Radcliffe Line sliced through Gurdaspur district. It was the only district that was divided tehsil-wise.

(David Devadas is a journalist and security, politics and geopolitics analyst.)

Disclaimer: Views expressed above are the author’s own.