In December 1971, as the Indian Army tightened its noose against the Pakistani Army around Dhaka, then US president Richard Nixon asked his secretary of state Henry Kissinger to ask the Chinese if they could move, or threaten to move some forces to deter India from crushing Pakistani forces in the east. “They got to threaten or they got to move; one of the two” was Nixon’s explicit message. As the situation worsened for Pakistan, Nixon told Kissinger “But damnit, I am convinced that if the Chinese start moving, the Indians will be petrified”.

It was an era of the cold war when Indian-Soviet relations were at their peak, and India, despite being a democracy, was perceived as a threat by the West. As the Chinese promptly refused and despite the threat of escalation, the West ultimately stood down, fearing that the Soviet response could trigger a larger conflict. From there on, the history is well documented on how the China-Pak-US axis played out in Asia much to counterbalance the rise of India in the region. The eruption of insurgency in Kashmir and the rise of the Taliban are all part of the same play.

After the Balakote strike in 2019, the Indian and Pakistani armies stood in a tense stand-off along their border. During this period, the US was planning the withdrawal of its troops from Afghanistan. In February 2020, they reached an agreement with the Taliban on the withdrawal of troops which was set for the following year. By May 2020, the Indian and Chinese forces were involved in a series of clashes around the Galwan valley in the border region of Ladakh. The idea was to petrify the Indians but that era had changed. The Chinese ended up with more than a bloody nose and a long stand-off ensued.

As India moved to reposition its forces from its western border towards the north and north-eastern border to counter the Chinese threat, Pakistan got ample time to realign its forces on the border with Afghanistan. A year later, Pakistan provided full support to the Taliban in taking control of Afghanistan after US troops withdrew from Kabul, leaving the power with the hardcore Islamist forces. Subsequently after a tense faceoff for more than a year, the Chinese ultimately reached an agreement with the Indian government and the stand-off largely ended. The US was able to meet its strategic goal of handing over power to the Taliban by covertly supporting Pakistan through China. The Nixon-Kissinger policy of deterring India through China was still very much in play.

Since 2018, India has been expanding its role in the South Asian region as an emerging power. New Delhi’s way of adopting an autonomous approach by using a multipolar model for engaging with foreign partners for its own strategic and economic benefits has worked well. It has earned India global respect and projected it as a responsible emerging nation. On one hand, India worked closely with the US and its allies in Afghanistan; on the other hand, India along with Iran, Russia and other Central Asian countries was working together towards an increasing role in Afghanistan.

India’s multipolar approach hasn’t augured well for Washington DC, as both Iran and Russia are viewed as serious potential threats by the US. The US-conceived Indo-Pacific strategic policy traditionally tilts towards China with the intent to keep Russia and Iran under check. Moreover, its strategic investment in Pakistan gives it unprecedented leverage in the region. The US also counterbalances the rising influence of India in the region by leveraging the Pakistan- China axis for its strategic benefits.

The world is currently in turmoil due to the Russia-Ukraine war. It has created an unprecedented energy crisis in Europe and in the rest of the world. The result has been high inflation across European countries, the UK and the US owing to the soaring oil and gas prices. European countries bear the maximum brunt of this crisis. With the onset of winter, the gas shortage crisis is going to hit Europe the most and is expected to have a devastating effect on its citizens.

As the US and the West imposed severe economic sanctions on Russia, the opportunity to buy oil and gas at cheaper prices opened up for other countries. The decision of India to abstain from the UN Security Council vote against Russia and of buying cheap Russian oil irked the US and its European allies. They had expected India to toe the line, and India’s refusal unsurprisingly triggered a textbook response from them. They predictively started supporting Pakistan, which has traditionally been a NATO ally and has supplied weapons to Ukraine against Russia recently.

The release of an IMF loan of $1.1 billion to save Pakistan from a complete economic collapse was the first step. It was followed by the release of $450 million package for the upkeep of Pakistan’s F16 fighter aircraft. The US ambassador to Pakistan’s visit to Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (PoJK), which US officials very vocally termed

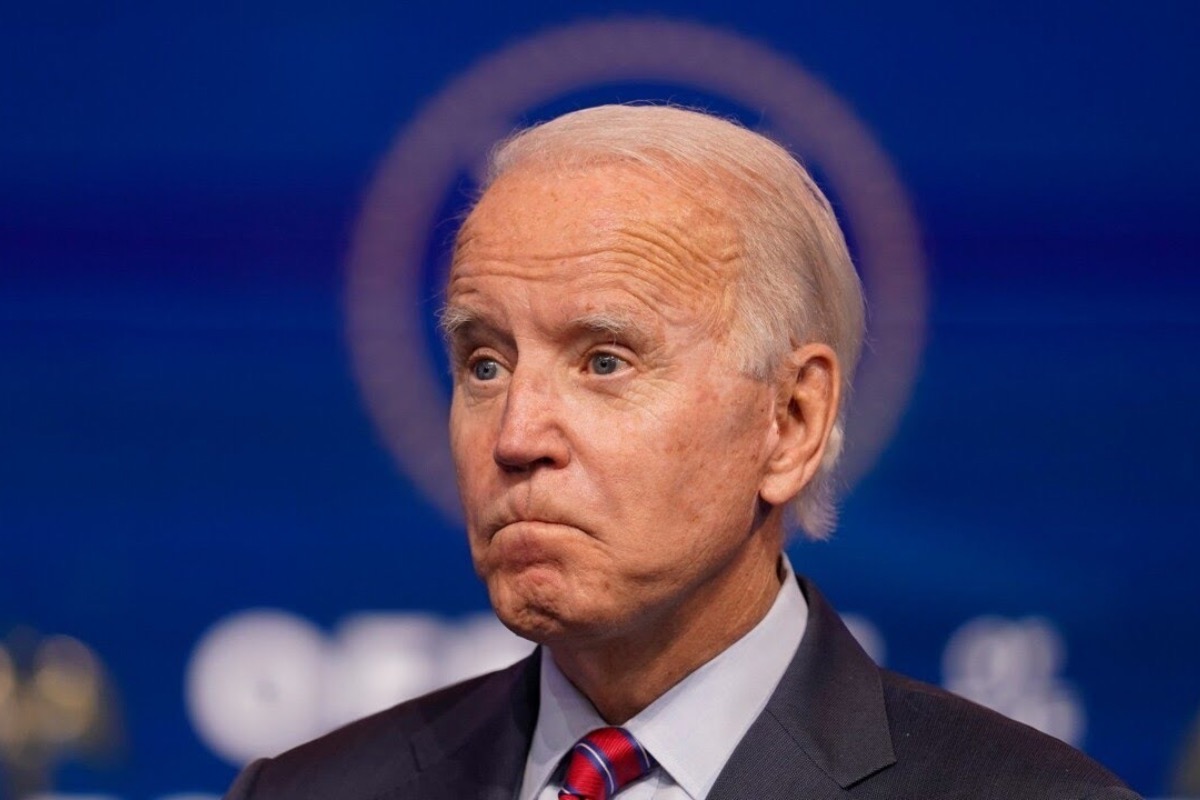

as AJK (Azad Jammu and Kashmir), was clearly a signal for India on upsetting its claim on POJK and the rest of an integral part of Jammu and Kashmir. The Himalayan region has traditionally been used as a beating drum of convenience for Western powers to arm-twist India internationally for their own strategic benefits. So, a sudden flare-up in cross-border terrorism or along LoC (Line of Control) is a huge possibility in near future. There are reports of Pakistan rapidly arming terrorists with small arms left behind by the US in Afghanistan to infiltrate the Indian border into Jammu and Kashmir. The probable removal of Pakistan from the FATF grey list is also another measure of adding irritant towards India. Surprisingly it is coming at a time when US president Joe Biden has called Pakistan the “most dangerous country” with nuclear weapons and no cohesion.

These moves suit China as it looks to rebuild its slowing economy back. It also gives Xi Jinping time to get elected for the third consecutive time hence strengthening his iron grip on China and pursuing the mutually laid policy of weakened Russia together. Despite these moves to throw India off balance, the geo-political churning happening in Afghanistan and Taiwan is expected to dent the US in the region more in the coming times. The West will be facing a much emboldened China in the eastern Pacific and an increasing radical Islamite terrorism threat emanating from Afghanistan. With China keeping its eyes firmly on consolidation in Taiwan, it will be unwilling to overly play the Pakistani misadventure games at the behest of the US. The US is set to lose its game against India as its supremacy will be further challenged in South Asia.

The Russia-Ukraine war is set to linger on through the winter. And as the energy crisis deepens further, the equation between the US and Europe is set to change. US foreign policy has always been aligned with the interests of the US alone. As Henry Kissinger famously said “America has no permanent friends or enemies, only interests”, other countries have taken the same cue and followed their own interests.

As the world is increasingly reluctant to play the great American game, it is time for Americans to respect the rules of their own game. By fuelling the endless wars of the military-industrial complex, America may sustain its dwindling economy for the time being but will ultimately bring a nuclear peril to the world.

As the new world order is set to lean more towards an autonomous multipolar direction, it’s the right opportunity to take a leaf from the Indian textbook of establishing stable multipolar relationships based on mutual respect, increased security and common economic benefits.