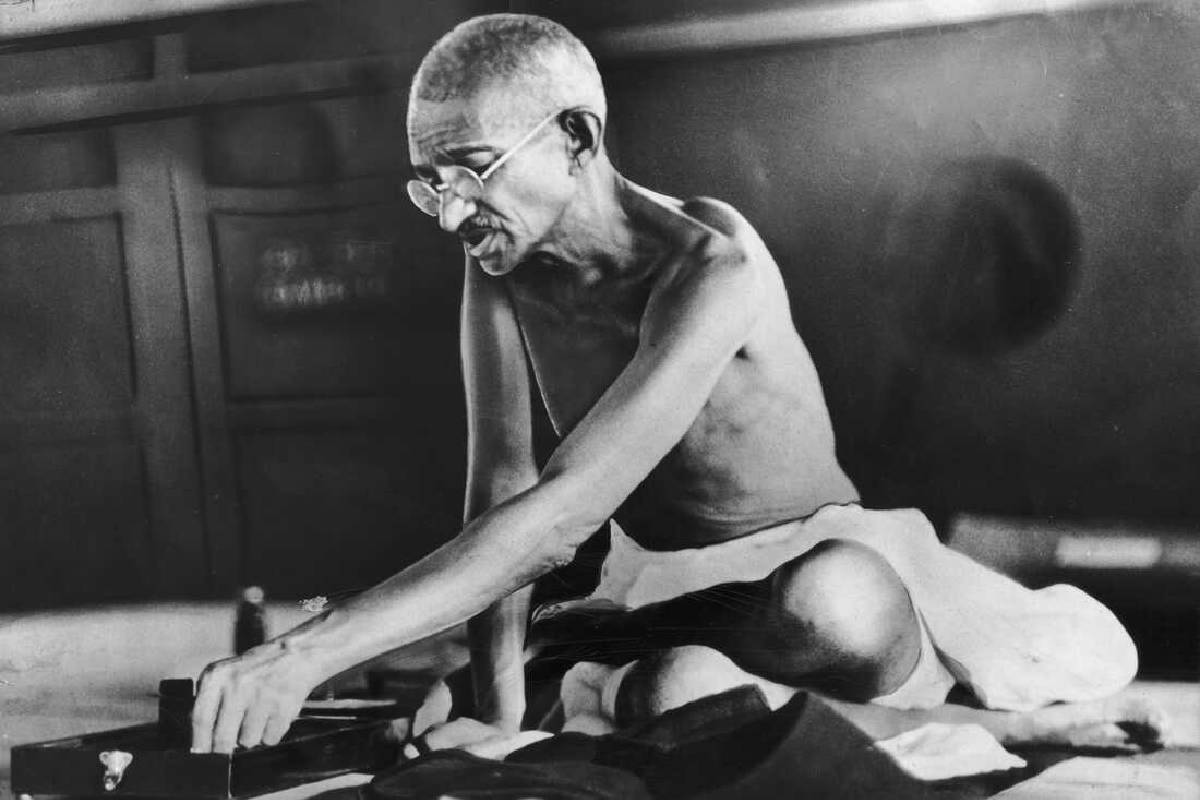

MK Gandhi was an influential figure of the 20th century and a peerless influence on India. Before him, mass politics, civil disobedience, and popular mobilisation, were largely unknown.

He singularly created a rousing new awakening and propagated reasoned anti-imperialist consciousness whose reverberations were felt from Gymkhanas of Delhi, to the drawing rooms of Malabar Hills, and from whisky-and-soda clubs of Tollygunge, to the dust-strewn, poverty stricken villages around Champaran.

Extraordinary mosaic

No figure in colonial Indian history helped people more to transcend their amoebic identities and tendency to splinter over minor differences or deviations.

READ MORE: Trudeau, Nijjar killing, and contours of American outlook

He was uniquely singular in the fact that ‘no political prophet of the 20th century led his life in such utter conformity to his ideals’, as mentioned by Dominique La Pierre and Larry Collins.

He also stood apart from others of his time by not subscribing to the ruthless amoralism of ‘Ends Justify Means’, or any form of Hobbesian state worship, vengeful, self-destructive Robbesperian haste or Leninist expedience.

His admirers, rather worshippers, abound in equal measure as his fervent detractors, who are all across the spectrum: left, right, liberal, conservative, libertarian, statist, nationalist, progressive, and reactionary.

Appellations and epithets bestowed on him range from the ancient Hindu honorific ‘Mahatma’ to the scornful ‘Seditious Fakir’ by arch British imperialist Winston Churchill, to ‘Fake Leader & False Prophet’, by the former Soviet Commissar of War and patron saint of international revolution, Leon Trotsky.

Just like Gandhism, which has been contorted beyond recognition to become pre-fabricated into any mould, most interpretations of Gandhi are rather piecemeal and tendentiously inadequate.

He’s lambasted by Ambedkarite identitarians for being a closet casteist and upholder of Hindu religious order, and simultaneously reviled by the ultra-right wing for covertly seeking to demolish Hindu religious order.

Leftists see him as a ‘safety valve comprador’, and liberals and libertarians as someone inextricably bogged under the morass of retrograde Indian village life.

The range of hostile reactions and frenzied responses are typically myopic and often fail to grasp the big picture.

Winds from the West

Nobel laureate VS Naipaul called Gandhi ‘the most Un-Indian of all Indian leaders’. Gandhi imbued not only a new way of thinking and seeing into the masses, but roused them from their historic inertia, and vegetative religious slumber, where metaphysical resignation, submission, and fatalism as a reckoning with destiny had become a collectively ingrained way of life. This was a passive degeneration of Karma, not an active belief in it.

Mass non-cooperation, collective defiance, civic solidarity, and resistance, of any sort, were not in the vocabulary of modern India before Gandhi.

It was a country that didn’t know social rebellion, or how to distinguish it from individual heroism, as Naipaul described in his scathing first travelogue on India ‘Area of Darkness’ in 1964.

In a culture and nation which despite its historic connections and trade networks from Malacca to Samarkand, had become so insular, inward looking, and afraid of new learning and change, where crossing the seas was considered a sin, his vast experiences and eclectic sources were tantamount to breaking new ground.

By seeking inspiration from Leo Tolstoy, Henry David Thoreau, John Ruskin, and tenets of Westminster law and western social contract, and being revolted by his South African experience, he became an internationalist and cosmopolitan.

There were many others as well in his milieu. But what sets him apart is that he didn’t restrict himself either to preaching to the choir, or hobnobbing and back-patting exclusively among selected cliques, or working for the acclaim of selected circles, as is largely the norm even today.

Expatriation for him was an odyssey of self-discovery, civilizational awakening, and absorbing waves of new thinking and ideas, which he ingeniously adapted to simple patois, keeping in mind Indian social conditions and grassroot reality.

Though Gandhians in India have largely been either self-serving politicians or khadi and homespun fetishists, his global acolytes range from writers, thinkers, reformists, and revolutionaries as well as ‘men of action’ like Romain Rolland, George Bernard Shaw, and William Somerset Maugham, Martin Luther King Junior, Nelson Mandela, and Ho Chi Minh.

There is nothing in common in this galaxy of Gandhi admirers, except their profound understanding of what afflicts their societies, and the need to blend theory and praxis, or as Nietzsche says, to harmonise vita activa and vita contemplativa.

READ MORE: LONG READ: Depp, Heard, and Netflix hyper-real

Re-affirming belonging

In 1960, Frank Moraes, a Goan Catholic, and among the first Indian editors of Times of India, visited Mao’s China as part of an official cultural delegation led by Vijaylakshmi Pandit, which also included Nehru’s brother-in-law, Raja Hutheesing, the Lucknow-based editor of National Herald at the time.

Moraes’ account of his visit, as well as the differences between the two giant neighbours are chronicled in ‘A Report on Mao’s China’, wherein he emphasizes the rapacity, plunder, and wanton destruction inflicted by colonialism, offering insights into how both countries think and work.

He underlines that demoralisation, cultural up-rootedness, and social destruction was excessively more in China as compared to India, due to a mix of competitive, freebooter colonialism, political disarray, award of concessions, there and the innate nature in social philosophies and outlooks.

“Despite years of subjugation, India had in Hinduism a system robust and resilient enough to draw strength from its own fountainhead”, writes Moraes.

“In China, the collapse of Confucianism created a vacuum in whose void the Chinese intellectual roamed, as one observer puts it, “like a displaced person emotionally and intellectually”. “Chinese thought, exposed to many conflicting blasts, suddenly found itself rootless”, he adds.

It was Gandhi who rejuvenated this eternal well-spring, precluding it from turning more stagnant and murkier, and tapping wholly into it as an ethical compass as well as a source of social and civilizational continuity and dynamism.

However, to use modern day corporate lingo, the tragedy of Gandhi was that he stood for what was a special purpose vehicle limited to mass mobilization, nationalistic consolidation, and throwing the yoke of colonialism.

Gandhism in post-colonial India turned into a mimic anti-modernity largely because of what Camus said: ‘What is an excellent reason for living, is often an excellent reason for dying’, which Naipaul also seconded.

Brilliant piece!