India’s Great Epic

Homer is credited with being the father of Western literature. We aren’t sure whether he lived or not but what has been recorded is that he was a bard who recited great tales based on events of the Trojan War which became known as ‘The Iliad‘. So important was this and his other tale, ‘The Odyssey‘, that some historians believe the Greeks adapted the Phoenician alphabet to create their own to preserve these tales in written form. When people set out to create high civilization, they ultimately require books and records to preserve their identity and pass it on to posterity.

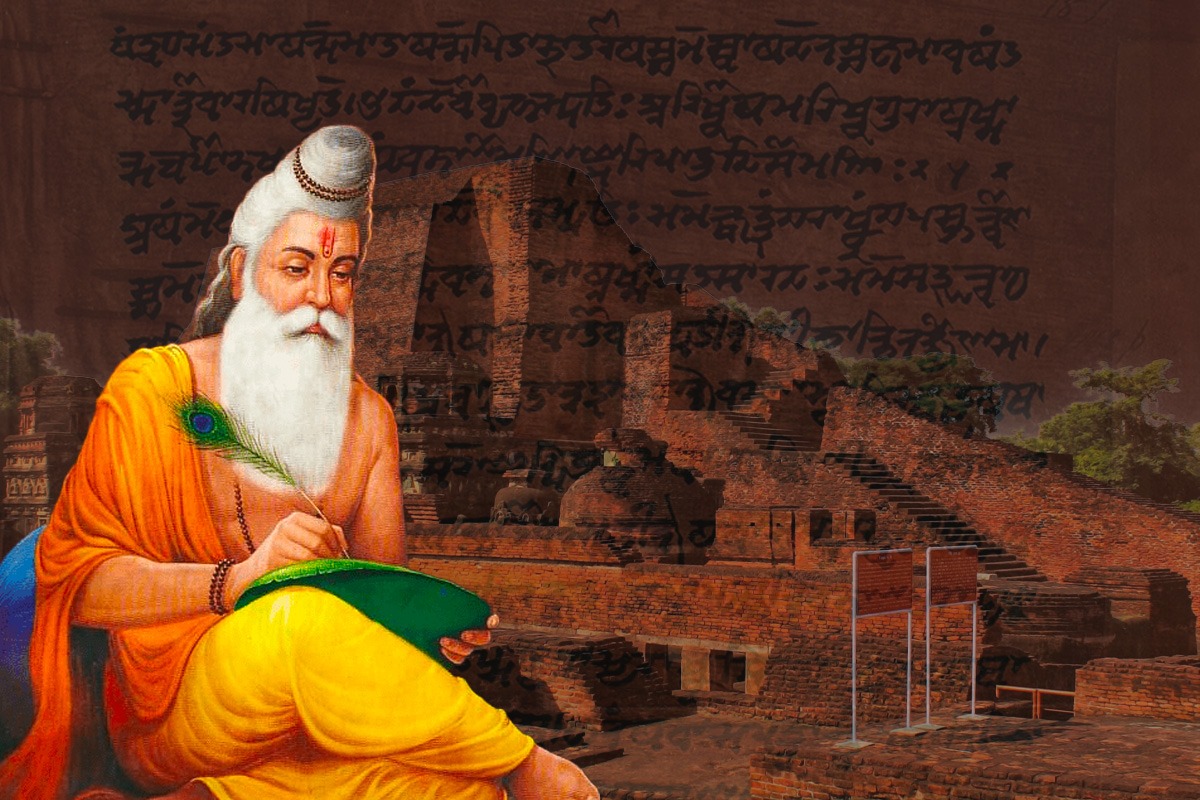

This occurred in most civilizations, the preserving of those narratives is considered important for any particular culture. In India there supposedly lived a rishi or sage named Vyasa who dwelled at the edge of a great forest. From there he was a witness to the battles and events between the powerful Pandava and Kausara clans who fought each other on the great plain of Kurukshetra. These battles and wars as well as the events surrounding the many characters in this epic became the very foundation of Indian epic literature, the myth that was at the heart of India’s civilization. Vyasa is said to have witnessed the battles and the events himself and as a consequence, he recorded the events in writing, which one day would become the great Mahabharata, a lengthy epic that still holds mass appeal for all Indians.

A tradition of spirituality and books

Vyasa is considered an important figure as he also divided the rather sumptuous religious text known as the Veda into four books, breaking it down so people can further study and research the teachings contained within and come to understand more intimately the meanings of the ‘suktas‘ or verses, as the corpus of the Veda in one book would be far too huge to consume as one text. The four Vedas are the Rig Veda, Samaveda, Yajurveda and the Atharveda.

Thus Vyasa earned his name because Vyasa in Sanskrit refers to dividing, splitting, and organising. Someone or perhaps a group of people decided to compile and organise the various sacred texts in this manner. Vyasa is also credited with compiling other religious books such as the 18 Puranas and the Brahma Sutras, important in the study of the Sanatan Dharma path which non-Indians know as a general term, Hinduism. Like the Greeks, the Indians gave the idea/person/group collaboration an identity, and named it as an individual, Vyasa. This is how the figure we can claim to be the father of Indian literature came to be known.

India was aptly termed by historian Michael Wood as ‘the Empire of the Spirit’. Every aspect of Indian life and thought revolves around the seeking of divinity and the place (or places?) of humanity, the gods, and the celestial beings in the universe, which is understood as a cyclical concept rather than the linear concept of time-associated with Zoroastrianism or the Abrahamic faiths. Wherever one travels in India, the sense of the otherworld is ever present, based on the concept of ‘maya‘, that all we see, hear, and touch in this dimension is but an illusion because what we see and experience now was experienced before and will be visible to future generations, as everything comes round over and over.

Indian civilizations have built great temples and architectural palaces, kingdoms went to war and seized land and wealth as anywhere and the kings of these many entities have known wealth beyond imagination. Yet Indian kings all understood that possessions are trivial compared to attaining enlightenment and divinity. The pursuit of divine knowledge permeates every aspect of Indian life and history. Therefore it is no surprise that this poet/bard Vyasa and his compilation of the great epic would be wrapped in a coating of Indian mysticism and otherworldly, celestial overtones. One of Vyasa’s disciples, Ugrashravas, is credited with being a great narrator of the Mahabharata who became a great teacher himself by explaining the various lessons that are taught and described in the epic. Ugrashravas can be said to have set the example for future sages to follow, his commentary further expounded upon century after century like the great rabbis and sages of Judaism who maintained a tradition of theological debate that continues to this day.

A Woman’s Touch?

As in the narratives of most ancient civilizations, there is an element of the otherworldly at play, for is said that Vyasa had some assistance from an apsara named Adrika. Apsaras are female celestial beings who inspire poets, dancers, musicians and artists, similar to the muses in ancient Greek mythology. Because the text of the Mahabharata was so long and there were so many events and personalities to keep track of, the apsara Adrika reminded Vyasa and assisted him in writing and preserving the epic, influencing even the language and the style of the verse. It was said that the verses are so bold and poignant, they could not have been written by a mere mortal. For example, the text is quite varied as it has some beautiful and tender passages of love and longing, even some laughter and comedy but also visceral descriptions of terrible battles that could compete with any violence found in ‘The Iliad‘, the Persian ‘Shah Nameh‘ or the Germanic Sagas for bloodshed and slaughter.

Yet it is all contained in the book, and Indian literary legend credits the apsara Adrika for bearing witness to the vicious battles, assisting Vyasa in compiling and preserving the events of the epic in a textual format. Perhaps the Mahabharata is the work of several authors, as is believed are the religious texts of the world, and the likelihood that it is the work of several authors is all the more evident in the days of yore when most people were illiterate and writing was the special reserve of the elite, who hired literate scholars to create such texts for them. The connection with other dimensions and realms was a common feature in the ancient world, intertwined in the life of India, beings from heaven having had a hand in the creation of such important texts.

Vyasa supposedly received visions and inspiration from Adrika, just as Arjuna sought guidance from Krishna. We have to wonder if a single male rishi or a group of men of an ancient, patriarchal India would have willingly composed the verses about the strong women of the Mahabharata such as Chitrangada, who defeats Arjuna in hand-to-hand combat and outdoes him in the art of archery, then takes him in and restores him to health, falls in love and bears him a son, who in time teaches this seeker of truth a lesson in karma and commitment- without giving a nod to the female apsara Adrika herself, who seemingly inspired Viyasa to write a few lines about women in a powerful light.

Or was Vyasa, or the more likely numerous authors of the text…just getting in touch with their feminine side? In Greek and Roman mythology, strong women are given their due mention but must be defeated, and are. In Indian epics, they are teachers in their own right, though they too must eventually take their seat in the shadow of men. Or, were some of the authors of the great epic women themselves? Apsaras are known in Indian literature and lore as dancing beauties who sometimes entice men or gods with their performance, sensuality and grace. Yet Adrika assists Vyasa in composing verses replete with visceral combat, as it is related that both she and he were witnesses to mighty battles and conflicts.

If she were a real person then we might compare her to Matilda, the wife of the Norman warlord William the Conqueror who subdued England after the famous battle of Hastings in 1066. The well-known Bayeux Tapestry depicts in art the exploits of her husband which includes the events leading up to and through the great battle. Though the tapestry is said to have been commissioned by one Bishop Odo, its execution was carried out under the direction of Matilda herself. Glancing at the tapestry we could see that Matilda, like Adrika, was no stranger to violence or the realities of warfare.

Vyasa may represent an example of the scholars of early India, at the commencement of the Vedic period when Indian culture and civilization were coming about and texts were being compiled. He may have been one person or a group of people the culture needed to identify to explain how their civilization and its thought developed. In what became a patriarchal society, of course, a man had to be the one to be remembered as the compiler of that society’s texts and scriptures. Yet India is amazing in that these narratives always include the feminine aspect.

If the apsara Adrika is a fictional character, then she represents the balance of male/female in the creative mind, much like the duality of gender associated with the god Shiva or even more importantly, as we read in the Rig Veda which explains that Shakti, the feminine essence of the universe, is responsible for organizing it all into both material and spiritual form. With that passage in the Rig Veda known as the Diva Sukta which describes the primordial source of the universe as the powerful and complete female, we understand why even in this patriarchal society the apsara Adrika is given her due in the history of the compiling of India’s great epic, which is as popular today as it was in the glory days of ancient India’s courts and kingdoms.

As a mother is necessary to bring forth and nurture life, the apsara nurtures the poet and the artist, guiding them to create beauty to solidify the very foundations of civilization. The apsara Adrika is acknowledged in sculpture and art as well as in the narration and the recounting of the history of the epic and for being a guide to Vyasa that great bard and poet, the equivalent of Homer in ancient India.

Ismail Butera is a lifelong musician and historian, exploring the intertwining threads of ancient history, mythology, and world cultures through his project ‘Echoes Of Antiquity,’ blending composed recitations and traditional music from diverse civilizations.