NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court on Wednesday recommended that the Union government’s Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) create a comprehensive policy for the governance and management of sacred groves across the country. The Court emphasized the need to protect the rights of local communities and involve them in forest conservation.

A bench comprising Justices B R Gavai, S V N Bhatti, and Sandeep Mehta noted that India is home to thousands of community-protected forests known as ‘sacred groves.’ As part of this policy, the MoEFCC must develop a plan for a nationwide survey of these sacred groves to identify their area, location, and extent while marking their boundaries. The boundaries should be flexible to accommodate natural growth and expansion but protected against reduction due to agricultural activities, human habitation, deforestation, or other causes.

ALSO READ: First Ganges dolphin tagged in Assam for research

Sacred groves are known by different names across various regions, including Devban in Himachal Pradesh, Devarakadu in Karnataka, Kavu in Kerala, Sarna in Madhya Pradesh, Oran in Rajasthan, Devrai in Maharashtra, Umanglai in Manipur, Law Kyntang/Law Lyngdoh in Meghalaya, Devan/Deobhumi in Uttarakhand, Grantham in West Bengal, and Pavitra Vana in Andhra Pradesh.

The bench suggested that models like the Piplantri village of Rajasthan which successfully addresses social, economic, and environmental challenges through community-driven initiatives should be implemented and replicated nationwide. The National Forest Policy of 1988 highlights the importance of involving people with customary rights in forests to help protect and improve forest ecosystems as they depend on these forests for their livelihood.

Senior advocate K Parameshwar highlighted that sacred groves are managed differently across states with some overseen by village panchayats or local bodies and others relying solely on community traditions without formal governance.

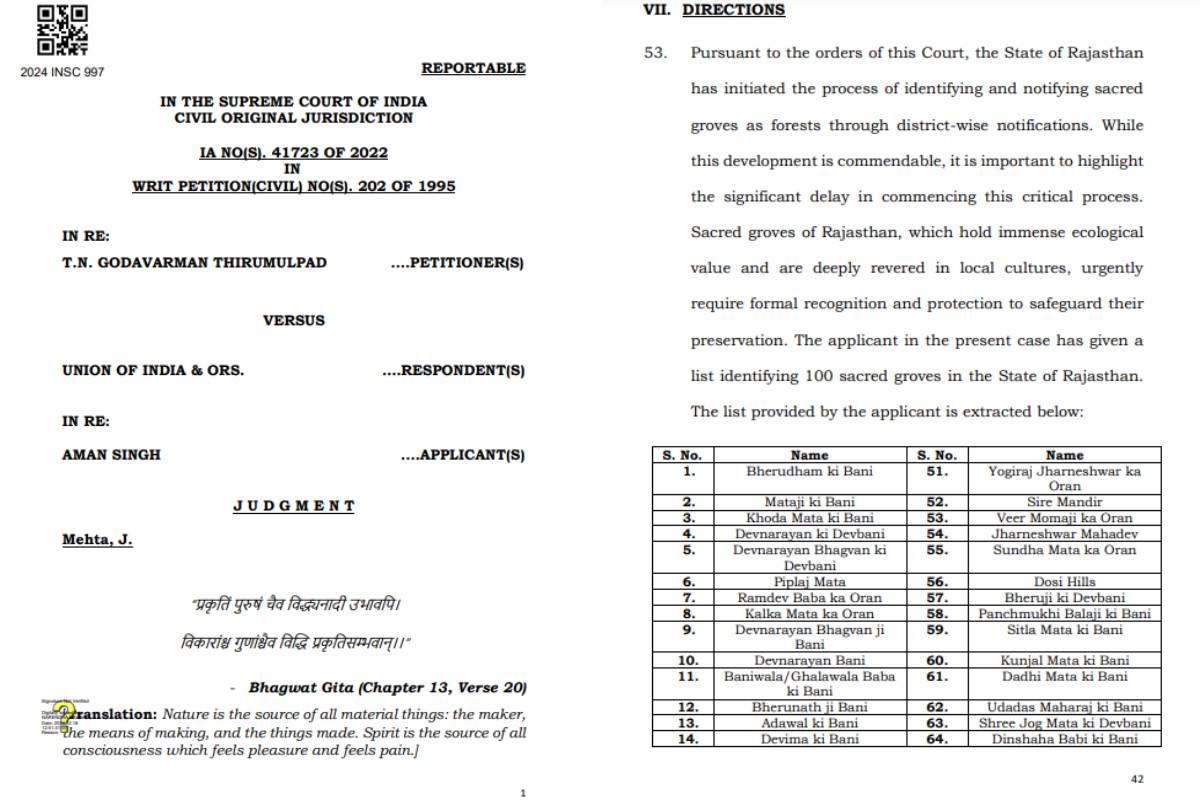

Dealing with an application filed by Aman Singh for the protection of ‘Orans,’ ‘Dev-vans,’ and ‘Rundhs,’ the Court directed that these areas be granted the legal status of ‘forest’ under the Forest (Conservation) Act considering their ecological, cultural, and spiritual significance. The state forest department was directed to carry out detailed on-ground and satellite mapping of each sacred grove and complete the survey and notification of sacred groves/Orans in all districts.

Given the ecological and cultural importance of sacred groves, the bench recommended that they be granted protection under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, specifically through Section 36-C, which allows for the declaration of ‘community reserves.’

ALSO READ: Rare Wroughton’s free-tailed bat species spotted in Delhi

The MoEFCC was directed to constitute a five-member committee with domain experts in collaboration with the state forest departments, preferably headed by a retired Judge of the Rajasthan High Court to ensure compliance with these directions.

The bench emphasized that active measures at the governmental level are required to ensure that models like Piplantri village are implemented and replicated to promote sustainable development and gender equality. The central and state governments should support these models by providing financial assistance, creating enabling policies, and offering technical guidance to communities.

The Piplantri model was created in a small village in Rajasthan’s Rajsamand district to demonstrate how environmental protection, gender equality, and economic growth can transform communities. Initiated by Sarpanch Shyam Sundar Paliwal, the practice of planting 111 trees for every girl born has significantly improved local biodiversity, increased the water table, and provided sustainable livelihoods, particularly for women. This model has also helped eliminate harmful practices like female foeticide and ensure education for all girls. By adopting and replicating successful models like Piplantri, India can promote sustainable development, conserve biodiversity, and protect the rights of forest-dependent communities.