I watched the Tamil version of Rocketry: The Nambi Effect last Sunday in a new and fine theatre with red push-back seats in Kottayi, a small village in Kerala’s Palakkad. At the lobby, they sold coffee and popcorn and all of it was just as good as anything in Delhi or Bombay, and you wondered how in the middle of nowhere — which you reached in the rain by car up a clean, narrow road with the greenery of the paddy fields opening up on either side in the rain mist and a buffalo in the distance still as a rock gazing at the deeper green forest of the palm trees bordering the livid purple of the horizon that he must go back to before the monsoon dark settled and things turned invisible — a technically-heavy narrative like Rocketry would be received.

It was received well. The hall was substantially occupied by children of Gulf returnees and farmers. No one walked out as Madhavan as Nambi Narayanan explained how he would effect a change in the rocket fuel technology in India in the 70s from solids to liquids at very low temperature because they were lighter and the propulsion impulse greater. As the movie progressed though, it was clear Madhavan with his engineering background, was obsessed more with the details of liquid propulsion/cryogenic technology than with the situation and character of his protagonist.

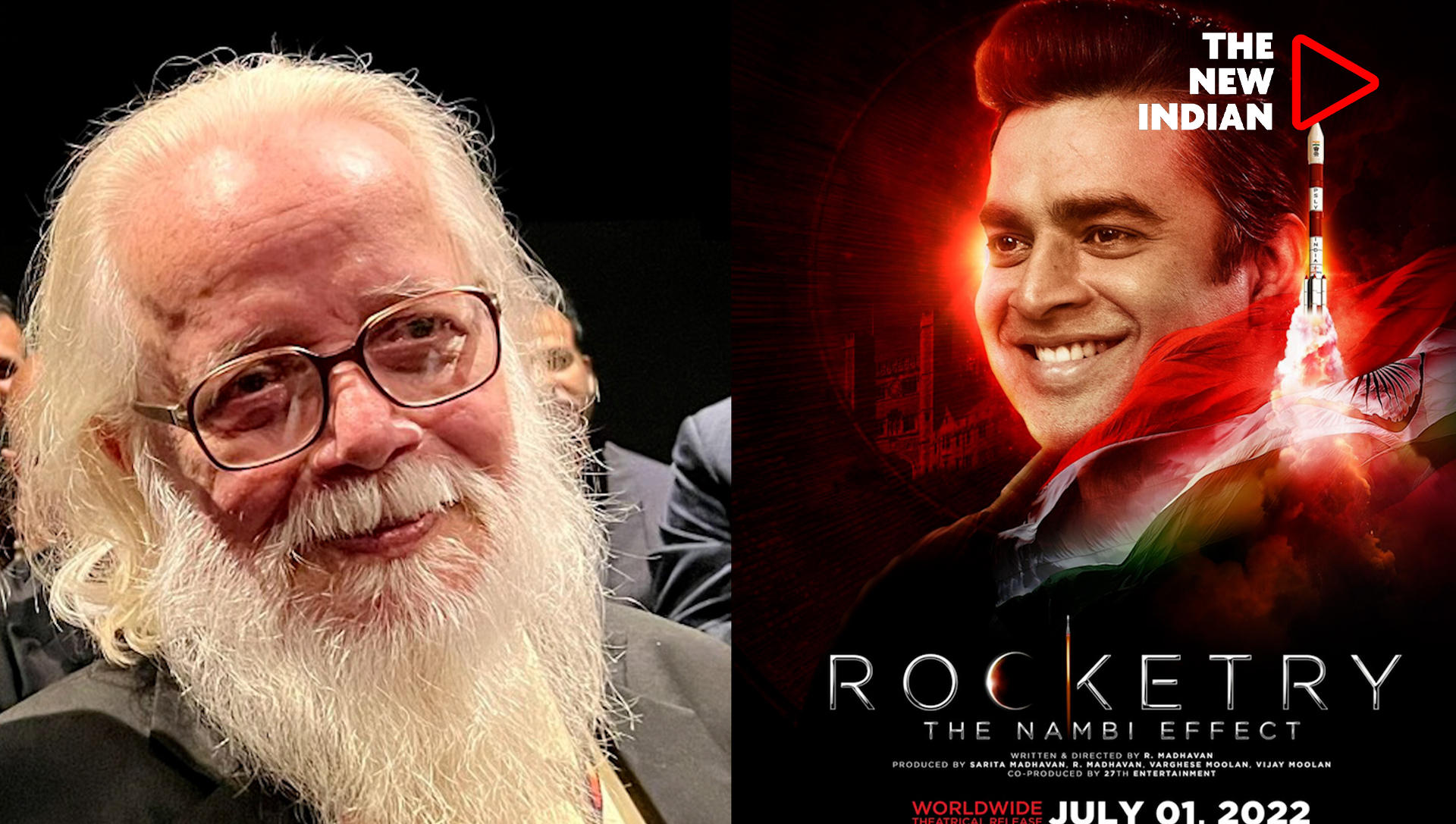

This is Madhavan’s first movie as a scriptwriter and director. And as one of the more intelligent artists in Indian cinema, he attempts bravely to be sensible about his subject. The movie begins very promisingly with the camera panning in a great seamless arc of the dark, starry skies and connecting the deep mystery of that unfathomable space to the little house of Nambi and his family in Trivandrum, before he is arrested on espionage charges. His wife, very well essayed by Simran, and children are subjected to hate campaigns and humiliation as the media paints Nambi as an espionage agent, having sold the secrets of Indian rocketry to Pakistan. Nambi is arrested and tortured and suffers ignominy for close to 30 years before he is cleared of all the charges by the Supreme Court, honored with civilian awards, and compensated monetarily by the Kerala and Indian governments.

The movie follows a non-linear path with many intercuts in the spine of the narration. That spine is a long, live TV interview with Nambi by Surya (in Tamil) and by Shah Rukh Khan in the Hindi version. In the end, on the screen, the real Nambi replaces Madhavan, and the biopic closes with the interviewer tearing up, going on his knees, and apologizing to Nambi on behalf of all who chose to misperceive him and laid his brilliance as a scientist to waste. Along with the interviewer, everybody in the studio also cries, and some among the audience in the Kottayi theatre as well. My eyes began to wet too, but then I remembered not without a little vengeance blooding it, and not for the first time that evening, the idea and the first treatment of the subject, numbering some 30-odd pages, were mine.

Unlike other movies in the mainstream, the brave, virtuous thing about Madhavan’s direction is that he makes the technology that Nambi helped develop and launch India into the very competitive space of commercial vehicle launch an instrument of drama. He also does justice to Nambi’s need to master it and put it to use to India’s benefit. The acquisition of that knowledge is riddled with challenges and problems for Nambi who comes from a lower-middle-class family and who is weaponized only by his fierce intelligence and ambition that burns as hot as rocket fuel. These aspects come into good play in the movie, and shore up the image of Nambi as a talent India trashed. And Madhavan as Nambi has done an excellent job.

But to turn a bio-pic into more than hagiography, a movie needs to show the great conflicts that a character finds himself caught in internally and externally. As a director, Madhavan falls just short of doing it. His awe of the genius of Nambi prevents him from showing the flaws (besides arrogance and cold professionalism) that ensnares him in a politically and socially sensitive situation, not of his making.

If not a parallel development, then at least a subplot, the Mariam Rasheeda factor in the espionage plot is completely missing. I know a little about the story because I reported on it as it broke, against the dominant trend in the national and international media that she was a spy, for The Metropolis on Saturday, and much later, in 2015, wrote a novel, Hadal, published by HarperCollins, when VK Karthika was the editor.

In 1994, Rasheeda, a Maldivian citizen, worked as a security officer of sorts. She had come for a personal visit to Trivandrum. She overstayed her visa and a police officer in charge of the visa extension allegedly asked for sexual favours as the price. Rasheeda, at this time, was seeing a fabrication engineer who had a contract with the ISRO, who was known to Nambi.

The spurned police officer arrested Rasheeda (who was tried and found guilty thanks to the media and the general uproar) and framed her as a spy. She spent five dark years away from her family in Viyyur Central Jail in Thrissur. She was poor, innocent, and ignorant. She had a smattering of English, and she haggled with hotels and auto-rickshaw drivers. Surely, the kind of things international espionage agents shied away from unless they wanted to draw attention to themselves.

Well, the fabrication engineer was arrested. To save his skin, he dragged Nambi who had a sterling reputation as a scientist. By now, the international media had descended on Trivandrum. A rocket spy scandal of global dimensions unfolding in a small coastal town was exactly what five-star reporters loved. It was paid vacation, and it was straight out of a Graham Green novel. Many careers would be made off it in the police force and the media and politics. And one of India’s best and proudest rocket scientists would pay the price for it.

In 2012, when I mentioned this idea to the director Ananth Mahadevan, he was excited. Soon after, I worked on a treatment that tried to do justice to the complexity of the subject and, on a sunny day, drove with Ananth Mahadevan from Cochin airport to meet the great actor Mohan Lal, who was shooting for Dhrishiam somewhere in Moovattupuzha. Nambi was with us. The meeting did not translate into a contract. A couple of years later, Ananth Mahadevan and I met Madhavan at his Kandivali apartment in Mumbai. He fell in love with the idea, accepted my treatment, and the next I know about it is Rocketry which I watched in Kottayi last Sunday, often shaking my head in disapproval at the one-dimensional simplicity of the narrative. But, for the now, well-known incidents in Nambi’s life and perhaps a skeletal framework, little of what I wrote is in it, or so I believe, and so I have no complaints, and I wish Madhavan and his movie well.

Rocketry is documentarist in its approach. Clearly, Madhavan reveres Nambi. But even where it is literal in its approach, the script is dialogue-heavy in a rather textbookish way, pulling the unsuspecting audience into technical details of rocketry that the director should know, but not necessarily show. As Hemingway said, if you know and leave out, the reader will get it. Madhavan is clearly not an exponent of the iceberg principle.

A possible CIA role in the conspiracy to frame Nambi and crashland India’s rocket program is hinted at, but not dramatically explored. Madhavan must fear that any deviation from the straight and the narrow will take the story away from the Nambi trajectory. Unfortunately, one of the great challenges of writing the script on the Nambi – ISRO (Indian Space Research Organization) story is the layering of the conspiracy.

The real problem with Rocketry is that it portrays the victim faithfully, but not the intrigue that wove the web and caught him at the centre. Perhaps Ananth Mahavedan will find a producer yet, and I will get to write about the spiders, and the sunlight filtering through the web of silk so fine only the fly knows it because it can’t move.

CP Surendran is a poet, novelist, screenplay writer, and columnist. He lives in Delhi.

(Disclaimer: Views expressed above are the author’s own.)