A Vedic Hymn To The Earth

O Earth, my Mother

Set thou me happily in a place secure

Of one accord with Heaven, O Sage

Set me in glory and wealth.

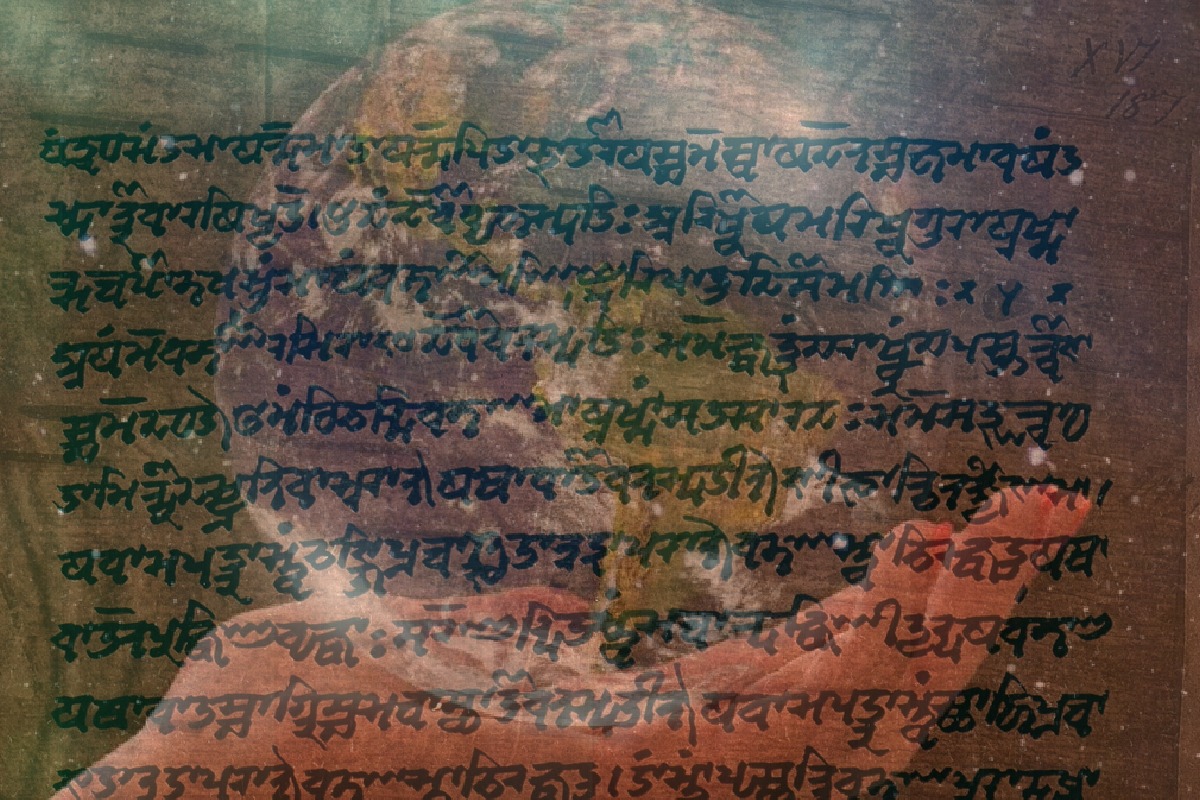

The Prithvi Sutka is a hymn found in the Atharva Veda, one of the four Vedas which are at the very foundation of Sanatan Dharma, a spiritual tradition native to India, known to the world as Hinduism. The Vedas are an established, codified compilation of beliefs, practices, rituals and spiritual conclusions which, along with such ancient texts as the Upanishads and Bhagavad Gita, are classed as among the great books of India in turn, among the great religious scriptures of humanity. Originally composed and handed down orally, the Vedas were written down as early as 1200-900 BC. The Vedas explain nearly everything about this life and the cosmos. They contain many Suktas or hymns, and many of them are extremely beautiful.

The Prithvi Sukta is a salutation to Mother Earth, the goddess Prithvi herself, acknowledging her beauty in nature and her pertinence and importance to humanity and all creatures. Such a Sukta surely inspired many gurus and rishis who saw themselves as caretakers of the Earth and established ashrams to take care of the land and its inhabitants be they human, animal, bird, reptile or insect. Compassion for humans develops out of a respect for the land, nature and our surroundings, which is a god-like quality inherent in all human beings.

Perhaps such verses inspired the likes of the emperor Ashoka who lived from 304-232 BC. He passed laws restricting the killing of animals and established ashrams that acted as clinics to assist wounded or sick animals. He established work teams that took care of the land and the rivers, planting banyan trees and mango groves and constructing nature-conscious rest houses for travellers along the roads. It should not be so surprising that Ashoka banned the death penalty for criminals. Rehabilitation was a goal far more productive than capital punishment. Reverence for the land yields reverence for fellow human beings.

What we in the West with our legacy of the Abrahamic and Persian/Zoroastrian linear time concept (a beginning, middle and an end) what we refer to as ‘eastern’ religion encourages a mindset that reflects the cyclical. For the followers of the Dharmic/Hindu paths, Buddhism, the Native American and African tribal religions or the Polynesians of the Pacific, humanity cannot perform something bad or distasteful in this life cycle and perhaps pray for forgiveness based on some good deed one has done while present in this lifetime. A cyclical inspired mindset understands that one lifetime of seventy, eighty or ninety years is not the end, but just another step in a long road to perfection.

The Abrahamic religions and Zoroastrianism speak of the expiation of sins based on a good deed or act, as the God of the universe is all-seeing and can forgive our sometimes reckless acts. Yet, when one understands our existence as part of a great spiral we are expected as imperfect beings to falter. We have many lifetimes to make up for our carelessness in the next life, the next, and so on. All of this mention of cyclical time and the great spiral of existence leads us to ponder as to why the followers of Hinduism, Buddhism and the world’s traditional religions have developed such reverence for all living creatures, developing whole texts dedicated to nature.

Native American belief systems acknowledge a Great Spirit but also think of animals, birds and even insects as brothers and members of a single family, all worshipping and praising the source of life, the Great Spirit which among the civilizations of the Maya, Aztecs and the Inca was manifested as the Sun. People living in these and other nature-religion societies hunted animals for food but did not overhunt them, which would be a logical means to preserve food for the future.

This is not meant to insinuate that Native societies were peaceful or that when they became kingdoms, they were compassionate or their organised religions demanded human sacrifice. But gluttony wasn’t a feature of their cultures and they used only what they required. While these more cultured societies became empires and surely burned down forests and cleared the land as in the case of the Maya, in some instances so effectively that they destroyed the environment and had to vacate the land they were living on, there were native Shamans among them who warned about the destruction of ‘mother’ Earth, referred among the Quechua of the Andes as ‘Pacha Mama’. The followers of the various spiritual practices who adhere to this cyclical mindset think as being not above the Earth, but part of it. We are not above life, we are a portion of the very life cycle itself. We are the rain and the rain is us, as is the Earth.

The same can be said for the followers of India’s Dharmic path who, many millennia before wrote treatises about the need to preserve the Earth and the forests, the trees and all living things, as we witness when reading and studying the Prithvi Sukta and a host of other texts written by rishis of the past dealing with the importance of respecting nature. Even a mountain is considered a living being, as are rivers and streams, fields and waterfalls, in fact, all of nature. Please think of the Ganges and why millions flock to it to bathe along its banks, ignoring the inconvenience of the crowds.

It is an ancient spiritual belief to be one with nature and one can say this is a universal belief, for even Zoroaster contemplated alone in nature, Jesus frequented the wilderness, and Mohammed contemplated divinity within a cave, all of them doing exactly what gurus and rishis have done in India for thousands of years. If being alone in nature gives us peace and helps us attain enlightenment and understanding then it might do us well to imitate the sages of India and experience for ourselves what nature can do for us, how it might heal us or bring us closer to understanding. It is said that Siddartha whom we would come to know as Gautama Buddha, became so lost in meditation that the tree under which he sat grew branches that entwined and twisted themselves around him.

In the Dharmic tradition, the song of a bird might seem like a revelation, the appearance of a brightly coloured insect a means for conveying teaching, the howl of a dog or wolf at night an echo of a heavenly song, the branches of that tree ensnaring Siddhartha perhaps equivalent to the arms of the Divine being embracing the devotee. Nothing is sure, but we all might agree today that caring for our world is like caring for ourselves. As far as we know it’s our home while we dally here in this life cycle, in this dimension. Therefore allow me to give a salutation, a Pranam if you will, to the ancient authors of the Prithvi Sukta, who remind us eternally of the responsibility of caring for our home, our cradle, and our mother, the Earth itself.

Ismail Butera is a lifelong musician and historian, exploring the intertwining threads of ancient history, mythology, and world cultures through his project ‘Echoes Of Antiquity,’ blending composed recitations and traditional music from diverse civilizations.