Ever since China brokered the diplomatic breakthroughs between Saudi Arabia and Iran, there has been a flood of commentaries from both ends of the spectrum: those that consider this to be a significant achievement, and those that do not. There is also a third fringe – a section in the West – that has taken to speculating how the deal could benefit the USA.

These are important lines of thought. And they have encouraged me to also make a guess about the future; which explains the headline of this article. However, in order to get there, let us first understand a bit about China’s Saudi-Iran deal, and its possible immediate impact in the region as well as on those states that are watching it keenly.

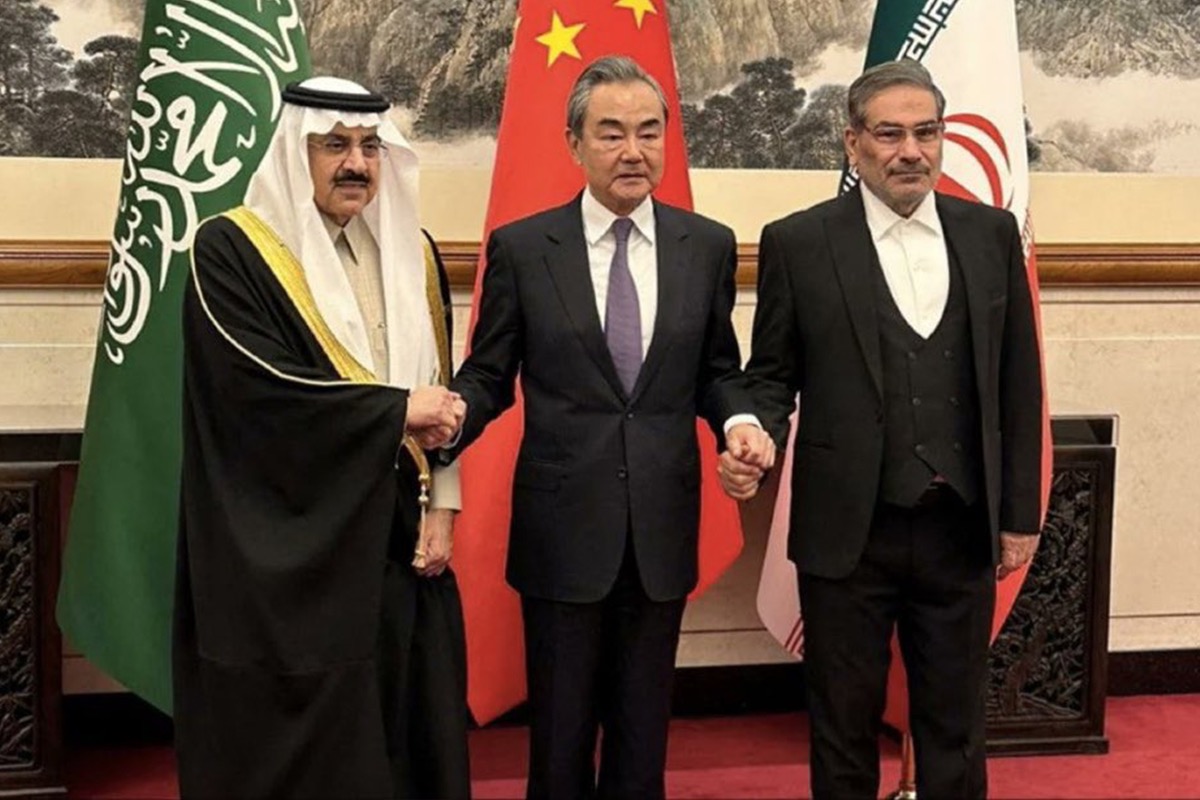

This deal is perhaps one of the two – Abraham Accords being the other – biggest reconciliation initiatives between two major opposing forces in the Gulf. While the Abraham Accords was between Israel and UAE, this one is between Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran – two nations with sectarian differences that are too deep, too fundamental, and that can be traced back more than a thousand years. China played host to a series of meetings and discussions between the representatives of these two states – a portion of this was initiated sometime towards the end of 2022 – and now Iran and Saudi Arabia have decided to reopen their embassies in each other’s countries and resume diplomatic relations.

Does this deal mean that Iran and Saudi would forget all about being Shia or Sunni and it would be a journey of peace and brotherhood into the future? Short answer: no. This is only the first step towards an acknowledgment of the fact that there could after all be a couple of common areas of interest between these two states. At this stage, it is more like two conflict-bound nations carefully evaluating the chances of a transactional interdependence of sorts.

There is a hint that this deal might help bring about an end to the civil war that is raging in Yemen and has been bleeding Saudi Arabia for a few years now. That war is between the Saudi-backed Yemeni government forces and Iran-backed Houthi rebels. If that transpires, then that could be suggestive of these countries focussing on harnessing their respective strengths.

Between Iran and Saudi, while the former has a more armed presence in the entire region through different proxies and militia groups, the latter enjoys a stronger economy. If China or Saudi Arabia agreed to look into the economy of sanction-affected Iran (though at this point, this is only an assumption) – through direct investments or otherwise, Iran could lessen its support to the different proxies and militia groups operating in different countries like Yemen Lebanon or Syria, and even in Saudi and Bahrain.

There are many other areas of concern. Analysts think that if a few of these are picked and addressed locally as the relationship develops, it could heighten the prospect of relative calm in the Middle East – something that has eluded the region for a long time now.

Is this a big deal? Or, is it just optics?

On its own and at this stage, the deal conceivably does not cover much, and those that think this is primarily optics would perhaps be right. Iran and Saudi Arabia, as mentioned before, are fundamentally different from each other; the fault line between them cannot be resolved as long as they adhere to their respective versions of Islam.

The impact of this deal however alters radically if the focus diverts to the dealmaker. China, through a successful Saudi-Iran diplomatic intervention, has pointed out a low-competence area of the USA. The US, with the kind of relations that it has within the Middle East, could never have brokered something like this. Incidentally, it is not just because of its present relations with Iran. The Obama years witnessed a heightened interest in Iran. But there was no deal because this sudden Iran affinity had come at the cost of alienating Saudi Arabia.

This incapability (or unwillingness) of the US towards genuine diplomatic efforts gave rise to what I call the Middle Eastern see-saw, and that is something that China is willing to address. It is safe to assume that there are a couple of similar areas around the world that China can and will wade into. Like Ukraine.

Zelensky has been continuously asking for a face-to-face with Xi. The latest update is that Xi has finally agreed to a video conference (to be held sometime within the next 7-10 days). On the off chance that the discussion veers towards Ukrainian negotiations with Russia, that would poke the US in its eye to mark another one of its no-go areas.

Through building infrastructure and investing in economies in areas near and far, China has consolidated its image as a non-interfering business-only partner that has little to no interest in the internal affairs of a nation – no matter how transparent or opaque the host nation’s governance is. (China’s neighbourhood would have a different story to say; but that does not affect the image of China in the Middle East, Africa, or South America).

Coming back to the USA, it looks like playing around the world with a win-lose agenda is gradually reaching its limits.

If in the near future, China wants to (and China most definitely would) pick and choose those American blindsides to leverage its image as a global negotiator, then this Iran-Saudi deal would look like the tip of a fairly large iceberg.

And apparently disconnected pictures, like Mexico wanting to join the BRICS, would gravitate towards that figurative iceberg to add to its volume.

Back to the headline of this article – if and when that happens, that might result in a globe with two dominant powers. Once again.

This preference and acceptance of diplomacy as a solution to conflict and chaos, or the tendency to look up to China as an alternative to the USA at the different negotiation tables, hint towards the return of a bipolar global structure.

It may not be as overt as the post-WWII one with its defined rules of membership and engagements, but it could very well result in a global setup where some of the mutually connected powers remained more than equal and exercised a degree of covert influence over the lesser ones. [Think Russia and China: two friends and allies, but China enjoys the upper hand].

Assuming that rules would be decided among the two biggest contenders, China has a good lead already over countries like Russia, India, or the Japan-Germany-France trio (countries that the USA considers its subordinates) in the race to the top where sits the USA. It is like the story of two friends in a jungle being chased by a tiger. The first friend says, ‘You cannot outrun a tiger!’ to which the second one replies, ‘True; I just have to outrun you’. China is that second friend to Russia, India or Japan, and Germany.