Human suffering and pain defy measurement; tragedies resist quantification. Yet, six years ago, economist Swaminathan Aiyer, renowned for ‘Swaminomics,’ undertook an unusual accounting—comparing two cases of ethnic cleansing: the expulsion of Hindus (Pandits) from Kashmir in 1990 and Muslims from Jammu in 1947. Later, author of ‘Devil’s Advocate’, Karan Thapar echoed similar calculations, both concluding that the ethnic cleansing of Muslims from Jammu in 1947 was more tragic than that of Hindus from Kashmir in 1990. This arithmetical comparison, in an attempt to create a “secular” narrative, not only dehumanizes one set of victims but also trivializes their agony and nearly justifies their persecution.

What adds disingenuity to this insensitive calculus is that while there has been rightful spotlight on the cleansing of Muslims from Jammu, but there is complete erasure of the story of Hindus and Sikhs ethnically cleansed from Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (PoJK) and Gilgit Baltistan (GB) in 1947. Indian intelligentsia and scholars, whether due to cold, calculated political correctness post-independence or lack of interest or both, have participated in the burial of this crucial chapter in J&K’s history.

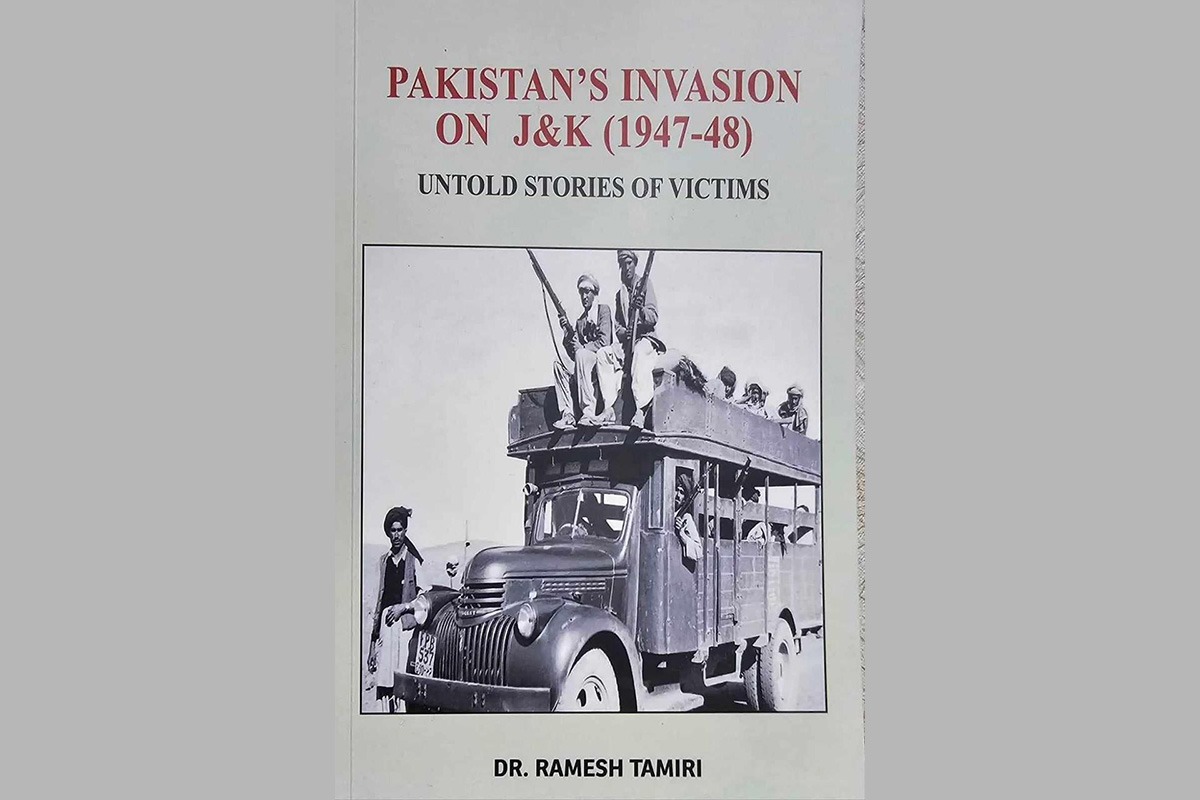

After 75 years, Dr. Ramesh Tamiri, a researcher and specialist on the history of Jammu & Kashmir, has filled a vast gap in the inquiry, investigation, and documentation of their story. In his recently published book, ‘Pakistan’s Invasion on J&K (1947-48): Untold Stories of Victims,’ Dr. Tamiri has not only pieced together the historical events of 1947-48 with clinical precision but has also unveiled critical facts, previously unknown.

The book authoritatively answers intriguing historical questions, such as—whether Maharaja Hari Singh or the then Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru is to be blamed for the delay in J&K’s accession to India. What was the role of British involvement in the invasion? Were Qaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah and then Prime Minister Liaqat Ali Khan aware of Pakistan’s invasion plan for J&K? What were the Congress party and the RSS doing at the time? With its highly nuanced and objective approach, the book has deconstructed many such questions and dismantled many myths built by political ecosystems over time.

The book provides groundbreaking information about half a dozen invasion plans conceived by Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership ahead of the Partition and sheds new light on the role of former INA officers, Ahmedis, Communists, and Americans during and after the invasion.

Above all, the book establishes that the Pakistan Army and tribal militia systematically orchestrated the ethnic cleansing of Hindus and Sikhs from PoJK and GB in 1947. The heartbreaking testimonies, in the book, reveal that the Pakistani invaders used abductions, rape, conversions, and forcible marriage as weapons of war against non-Muslim women. The stories of how women committed suicide to escape dishonour at the hands of invaders and how many women were sold later in cities of West Punjab and NWFP are gut-wrenching, to say the least.

The book diligently documents massacres in various places, including Alibeg camp in Mirpur which had been turned into an Auschwitz for Hindus and Sikhs. Over 38,000 minorities were killed by the invaders between 1947 and 1948 at various places in Muzaffarabad, Mirpur, Bhimber, Rajouri, Budhal, Chassana, Poonch, Skardu, Shigar, Ladakh, as per the testimonies and research material.

Each dark episode in human history deserves independent identification and recording, without diminishing the stories of other victims. One doesn’t need to incongruously and disingenuously, hyphenate the one-sided cleansing of Hindus from Kashmir in 1990 with the cleansing Muslims of Jammu in 1947. Each of these blemishes deserve their own truthful books and their own courageous story-tellers.

Dr. Tamiri’s work exemplifies this strength, narrating heartbreaking stories impartially. If the book includes testimonies of brutality by Muslim invaders, it also highlights acts of kindness and help by numerous Muslims. The author has painstakingly substantiated every assertion with proof and verifiable references.

Based on exhaustive interviews of hundreds of eyewitnesses and survivors conducted and preserved laboriously over two decades, Dr. Tamiri’s work is easily the finest specimen of both research and reportage, which should have been produced, as a moral duty, by the mainstream historians and media in the last 75 years. Though Dr. Tamiri has been a practising doctor, but the oral history backed by evidence and meticulous scholarship in his book, places him in the category of ‘People’s historian’ committed to fact-finding.

The hundreds of testimonies and dozens of photographs provided in the book will be of immense use to research scholars interested in the history of India, generally, and Jammu & Kashmir, particularly. Though the book is an easy read and will be of interest to general public, but it is a must read for scholars, historians and Indian policy makers and law makers.

The key to the ‘truth and reconciliation’ process, that the Supreme Court recently referred to in the context of Jammu & Kashmir’s history since 1947, while giving its verdict on the nullification of Articles 370 and 35A, lies in first establishing the truth. On January 19, when the displaced Kashmir Pandit Hindus observe their 34th year in exile from Kashmir, this book probably is the first step towards that process—a truth which had been unacknowledged so far, has been established.