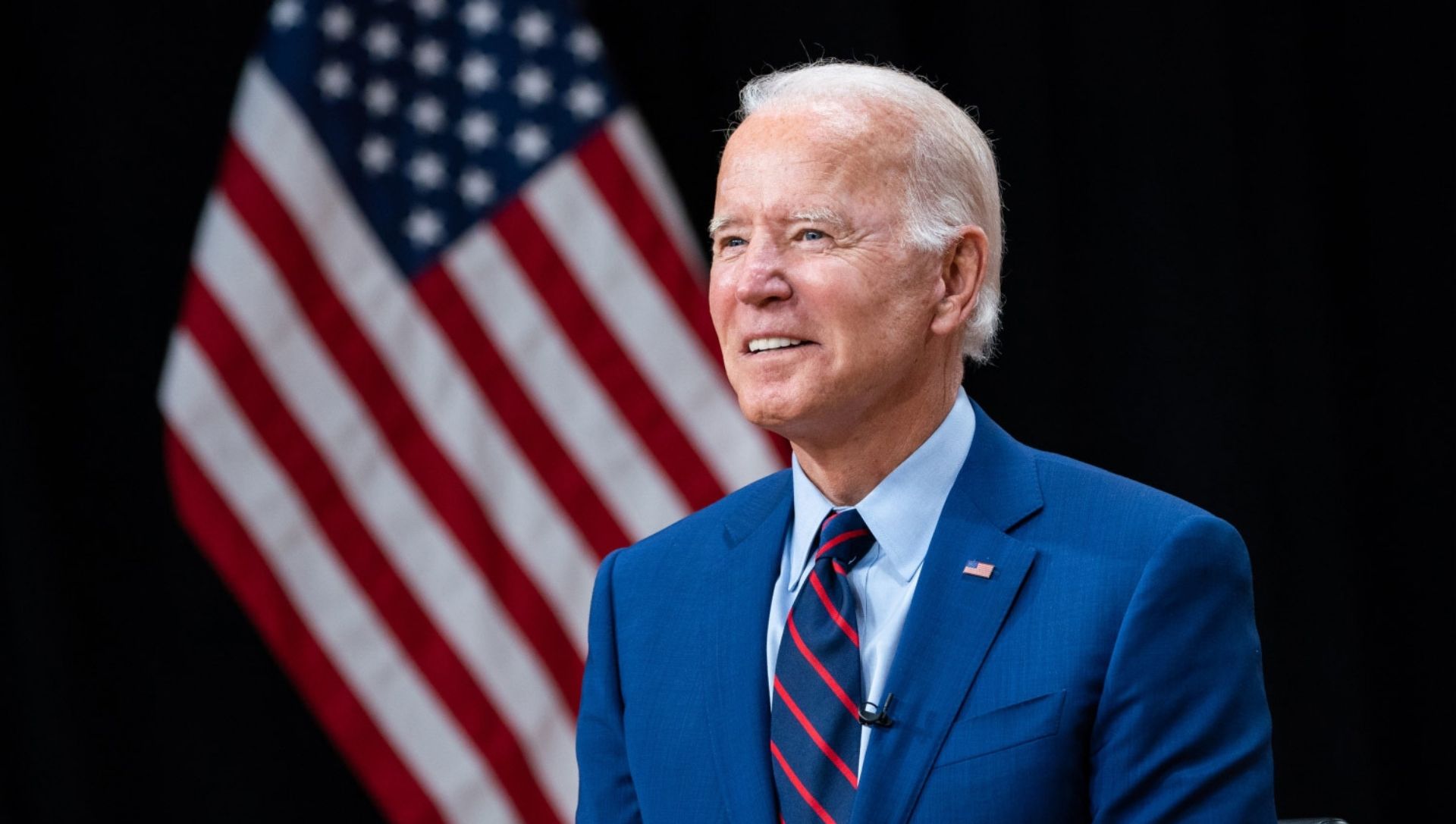

The hopes of US President Biden’s supporters when he took office have been dashed. The fears of those who thought the then 78-year old was already too advanced in years to provide a dynamic presidency have begun to seem well-founded.

His first priority—correctly—was to combat the pandemic. His administration rolled out vaccinations for US citizens with gusto, adding ‘booster’ third doses to the pan-national thrust. But the point about a pandemic is that it hops across the globe, scorning national borders. And as head of the world’s most powerful country, Biden failed the test of global leadership—to get vaccine producers to waive patents so that the entire world could be sufficiently vaccinated quickly enough to suppress the emergence of variants of concern.

Result: a vaccine-defying variant that originated from poorly vaccinated Africa has sent the US’s Covid infection graph rocketing in recent days, far higher than ever in the past two years. Sadly, it had another uptick after soaring and then plummeting, the way the Omicron-caused spike did in South Africa and the UK.

In short, Biden’s effort to curb Covid, his self-declared first priority, hasn’t quite worked.

Monetary injection

The US economy was doing well when Biden took over (if one ignores the quality of available employment), and he got Congress to pass a massive injection of government spending to rev up the post-Covid economy. But, since Covid is booming again instead, that effort remains on pause while the US national debt has soared even higher. Inflation is now galloping across the US.

Biden’s scheme was evidently meant to repeat FDR’s Keynesian boost. But the dynamic energy of that time (remember the ‘roaring 20s’ before the great crash?), and World War II, which followed, were key buoys of that project.

The spirit of the Gold Rush was still around, and people put their shoulder to the wheel. Amid today’s depressive pessimism, it would need the inspiring leadership of a JFK or a Lincoln to stir that spirit again—and I wonder if even that would work today. Certainly, Biden doesn’t have that charisma.

His often fissiparous party stuck loyally behind him during 2021, right across the programmatic divide between ‘Radical Left’ and Centrist. Yet, the White House has failed to get in-party consensus on electoral reforms that have life or death significance for Democrats. Two Democrat Congresspersons scuttled reform bills a few days ago.

The chance to pass such reforms emerged from the elections that brought Biden to power, and it is short-lived. For, most Pundits agree that the Democrats’ knife-edge majority in Congress can only go down when mid-term elections are held at year-end. So, Biden might even be presiding over the last hurrah of his party.

Afghan trauma

Biden’s inauguration exactly a year ago today was clouded by fears of violent resistance from those who refused to accept the election result, but his calm confidence in the efficiency of the established system to ensure a smooth transition was impressive in that phase. He was unruffled, as a leader should be, by the threat that Trump might refuse to leave the White House.

Within six months, however, expulsion from Afghanistan (yes, the US withdrawal looked a lot like expulsion) had robbed Biden of that aura of confident leadership. His ‘I want to talk about happy things, man,’ remark as he walked away from reporters asking about the Afghan disaster will linger mockingly.

For those of us who live across the world from the US, its seemingly chaotic exit from Afghanistan defines Biden’s presidency. It symbolised the US’s backing away from a leading role in not just south and Central Asia, but West Asia, and even continental Europe.

The West’s recent waffling over Russian aggressiveness towards Ukraine betokens Western indifference to what’s happening in Yemen, Syria, and Kazakhstan—not to speak of Ladakh and the rest of India’s eastern border. On 19 January, Biden showed a green light for ‘minor’ Russian aggression against Ukraine, talking of a response ‘proportionate’ to the extent of aggression. Ukraine’s leaders expressed shock. So should those who focus on India’s current border situation.

The US’s most decisive foreign policy move of the past year might be the promise of nuclear submarines to Australia as part of the newfound Australia-UK-US alliance. But I get the feeling that the UK was the prime mover of that. while Trump was still in power, there was talk of an alternative Anglo-Saxon (more trade-focused) alliance of Australia, the UK, Canada and New Zealand.

Those of us who take China’s vaulting ambitions seriously have begun to miss the bristling belligerence of Mike Pompeo, President Trump’s last Secretary of State. His obstreperous presence echoing across the globe might have grated then, but it reassured many.

Trying to keep all sides happy, and appeasing truculent power with niceness at a time when Xi and Putin’s respective revanchism threatens a dozen countries, is not foreign policy. From a country that seeks world status, it comes across a lot more like surrender. What was that about nice guys finishing last?

(David Devadas is the author of The Story of Kashmir and The Generation of Rage in Kashmir.)

[Disclaimer: The opinions, beliefs and views expressed by the author are personal.]